Anne's story

Anne Rigg

Clinical Director of Oncology

“We had quite a few difficult conversations with colleagues. If we continued to take patients, that meant fewer staff available to work in ITU. There was a lot of horse-trading.”

“We had to keep the cancer service going. The big worry was that patients were terrified to come in. The surgeons were anxious about their patients getting infected and dying. The operating theatres had been taken over by intensive care so we physically didn’t have the space. And we had to decide how to prioritise patients who absolutely needed chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

There were no cancer operations for the first 3 or 4 weeks. We were planning for the worst case scenario. There were massive unknowns at the start.

We had quite a few difficult conversations with colleagues. If we continued to take patients, that meant fewer staff available to work in ITU. There was a lot of horse-trading.

For the first couple of weeks we were figuring out how to categorise patients. We had to explain to those close to the end of life that because their cancer was so extensive if they got COVID-19 we wouldn’t resuscitate them or take them to ITU. Those were really difficult things to say to people you had been treating for years. We would normally have that conversation when they were in hospital but now we were having to have it at an earlier stage.

We made chemotherapy shorter and safer by altering the dose to minimise the number of times patients had to come into the hospital. They were all shielding. We were also more liberal with a drug to boost their white blood cells, to make them more resistant to infection. We use it sparingly because it is high cost but we decided this was a time not to worry about money.

Chemotherapy chairs were moved for patients to remain socially distanced

Chemotherapy chairs were moved for patients to remain socially distanced

“Instead of taking months to change the treatment regime we did it overnight. We had to crack on. It was transformative.”

We could safely delay radiotherapy for men with early prostate cancer by putting them on hormone therapy. For women having radiotherapy after breast cancer a trial had just been published showing 5 days at a higher dose was as effective as 15 days at a lower dose. Instead of taking months to implement that change we did it overnight. We had to crack on. It was transformative.

Staff continued to give radiotherapy wearing full PPE

Staff continued to give radiotherapy wearing full PPE

For surgery, there will have been patients who were delayed. We had a contract with the private London Bridge Hospital and moved surgery there. The surgeons started with the fittest patients and easiest cases to reassure themselves there wasn’t going to be a massive fatality rate. Tumours requiring an epic operation got delayed till they could see how things played out. Data from China had suggested 20% of patients were dying in the post-operative period. But with good infection control, things didn’t seem to be as deleterious as they had thought.

We have done 2,000 operations at London Bridge now. But because of the stringent infection control measures we only have half the capacity. We are going to need the independent sector for some time.

Everyone who needed chemotherapy and radiotherapy got it – in spite of COVID-19. That is, in the opinion of their treating doctor. Some patients at the end of life we had to explain the risk would be higher if they had extra treatment than if they didn’t.

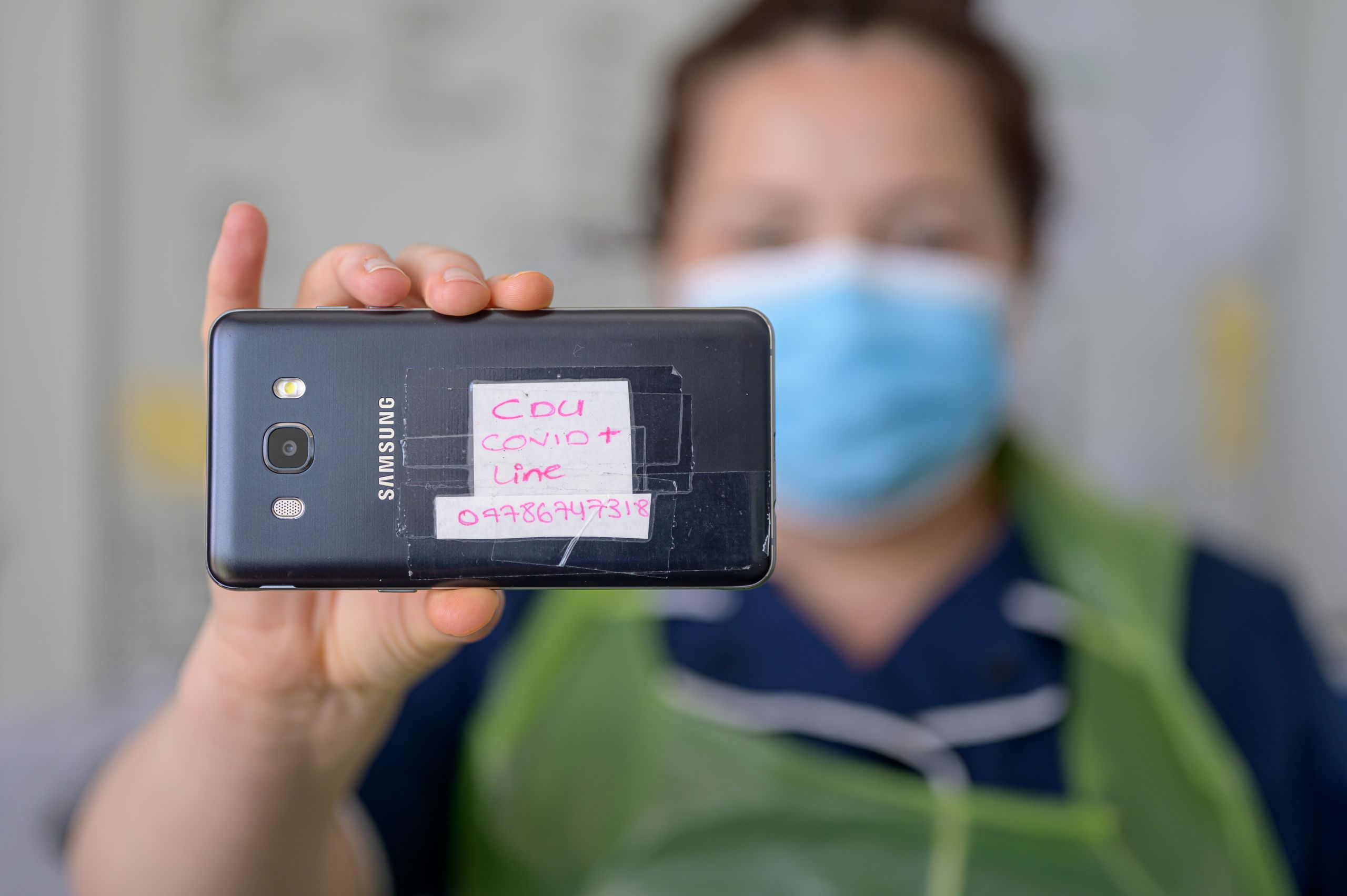

The COVID-19 phone line for the cancer centre

The COVID-19 phone line for the cancer centre

The delays to treatment for cancer patients are extremely worrying. A Lancet study by a colleague estimated there will be 3,500 premature deaths nationally in the next 5 years. We are very conscious of that and we are beginning to get a trickle of issues raised by relatives about what they consider delays.

“It was one of the best times of my career. All barriers to change were removed. The entire organisation was focused on keeping patients safe.”

We also had to close all our clinical trials - over 300. For patients who have run out of options it was very difficult. Inclusion in a trial could at least give them hope. We have kept meticulous notes of the changes we made. I truly believe we made the best decisions we could, based on the information available at the time.

The whole thing felt controlled and planned. I really, really enjoyed it. It was one of the best times of my career. All barriers to change were removed. Everything seemed possible. The entire organisation was focused on keeping patients safe.

The biggest challenge was communicating all the changes to my team. I felt the only way I could cope was if I was properly briefed and up to date. So I needed to do the same for my team.

We had a tactical meeting every day at 10am with 20-30 senior staff from all departments. People would raise problems and others would come up with the solutions – ‘Ok, we’ll send you a couple of extra doctors’, ‘We’ll organise a deep clean.’

At 1pm each day I met with my leadership team – we have over 400 staff in oncology. Every other day I led a briefing with the 64 consultants in oncology.

My proudest moment was when the Chief Executive called me at 8pm one evening and said he needed us to start testing patients for COVID-19. This was close to the end of April when Matt Hancock had pledged to raise testing to 100,000 a day. I said fine, we can do it next week. He said, I need you to start tomorrow. I gulped – but we did it. We did 20 tests the next day. We got up to 800 a week.

In April 2020 the cancer team started testing patients for COVID-19

In April 2020 the cancer team started testing patients for COVID-19

But I worried about my patients, especially in the early weeks when 1 in 10 staff were off. What if it got worse? If 50% were off we wouldn’t be able to do the work we do. There was an enormous sense of responsibility.

The vast majority of my colleagues got on with it, quietly and without fuss. A few were terribly risk averse and quite vocal about PPE, making me feel it was my personal fault that they weren’t getting better masks. I was anxious a lot of the time but I found it exciting. There were no rules and I liked that. But it didn’t suit others.

The cancer centre adapted to make it safer for patients and staff

The cancer centre adapted to make it safer for patients and staff

I did have a low 4 weeks ago. I felt absolutely exhausted. It shows you can’t continue with that level of energy and adrenaline indefinitely. There is far less appetite among the staff to do it again. But I said to them we are better prepared, better informed and we have created a much safer environment.

My husband is an army surgeon who has worked in war zones and tells amazing stories when we go out. I have always felt a bit dull beside him – that I had never been tested. Well, I have now.”

Read more stories